If you’re headed off on your great American road trip, you may be planning on visiting some of our wonderful national parks in the Southwest. If you’re planning on hiking, BE PREPARED!

Hiking in the desert is very different than hiking on mountain trails because the trails are often difficult to find, the summers are brutally hot, and the weather can be extremely dangerous. The desert is HOT, HIGH, and DRY. Though it is generally very safe to hike in the desert, you should not underestimate it!

I absolutely love hiking in the desert — there is something about the openness, the western landscape (think: twisted juniper trees and sandstone formations), and the crunch of the trail underneath my feet.

Keep on reading to find out the necessities of hiking in the desert.

Bring water may seem rather obvious: you’re in the dry desert after all! But don’t underestimate how much water to bring. Even on a rather short trail, such as Delicate Arch in Arches National Park (3 mi; 4.8 km), you may find yourself guzzling water due to lack of shade and the dry air.

We always bring our Camelbaks, one for the adults and one for the kids.

Also, pack salty snacks. It’s easy to think about water, but your body needs salt as well. Some people are so focused on water that they forget to eat, causing hyponatremia. This is rare, but you should be aware of it.

If you’re coming from a coastal or low-elevation climate, you may be surprised at how quickly you get winded.

Acclimating to the lack of oxygen can be a major issue for some people, especially if you’re hiking.

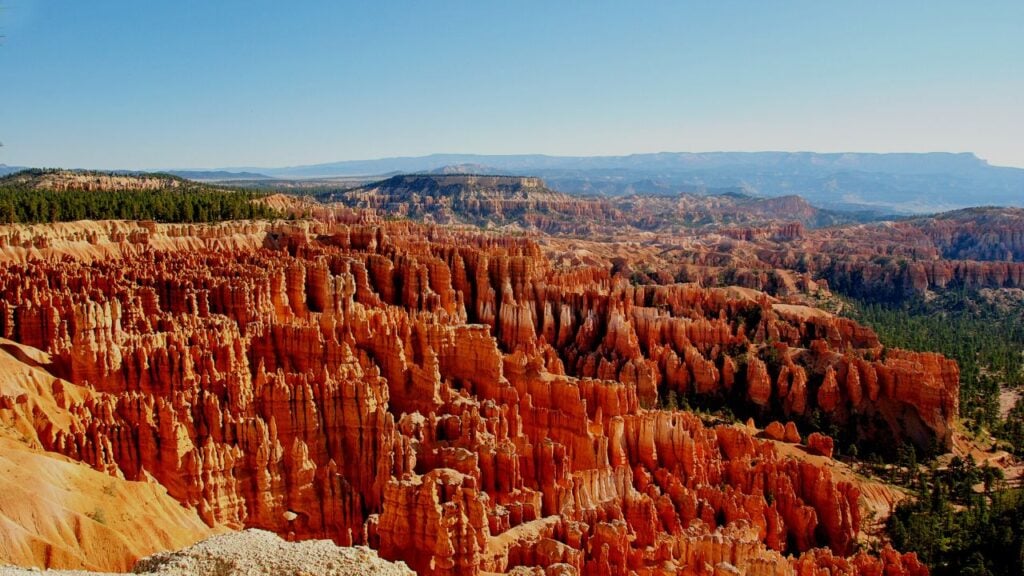

Though it’s a desert, the American Southwest is high elevation. Moab is over 4,000 feet above sea level; the Grand Canyon’s south rim is over 7,000 feet, and Bryce Canyon is an astounding 10,000 feet. It’s hard to believe these are desert climates, but they are.

You may want to consider packing an oxygen bottle with you in case you need a few puffs while hiking. It’s not a permanent solution but might provide some temporary relief.

Altitude sickness is actually a thing! While not common, some people get sick at these elevations. Sometimes the only solution is to leave and relocate to a lower elevation.

You may consider acclimating to the elevation before attempting a strenuous hike.

I know, I know, everyone thinks the weather in their part of the country or world can change in an instant. While this is mostly true, there are some unique things to consider about desert weather.

In the summer, the temperatures are HOT. While many dismiss this as a “dry heat,” it can still be insanely uncomfortable and even dangerous.

We visited Las Vegas when it was 117 degrees outside. All you can do when it’s that hot is run for cover indoors. It’s dangerous to be outside and even to drive in that kind of intense heat, as your vehicle could overheat.

Temperature swings are BIG and FAST. It’s common for temperatures to swing 40 degrees from night to day. You may start a hike while it’s nice and cool but find yourself wishing you brought a hat and water later on the same hike. You may start a hike in the afternoon with a T-shirt and shorts but wish you had brought a jacket after the sun goes down.

The desert has COLD winters and SNOW as well. If you’re visiting in the off-season or shoulder season, you might find yourself in a winter wonderland. Due to the high elevation, most places in the Southwest receive snow in the winter.

It can actually be very enjoyable to visit places like Zion, Bryce, and Arches in the winter, but be prepared with snow clothing and spikes for your shoes!

Always check the weather before starting your day: mid-day thunderstorms can turn your hike into a muddy mess, or worse, bring a flash flood (see below).

Again, don’t let the “dry heat” naysayers mislead you: the desert can be hot and exposed. It’s best to bring a wide-brimmed hat for shade. I wear a cowboy hat.

Many people wear long-sleeved shirts and pants when hiking in the desert, even in the middle of the hot season. I have never felt the need to do this, but experts will probably tell you it’s a good idea if you’re going to do a long hike with lots of sun exposure.

Sunglasses are a must for dealing with the bright desert sunshine!

We always bring layers of clothing when traveling. When the sun goes down at night, your sun-baked body might get chilled while sitting around the campsite.

Recently we started a hike to Corona Arch in Moab before sunrise and we were wearing a coat, beanie, and gloves. By the time we got to the arch the sun had risen and we were stripping layers.

Bring a backpack so you can store jackets, gloves, hats, chapstick, sunglasses, and sunscreen.

You’ll hear this term a lot in the desert, so it’s a good idea to know what it is and isn’t.

Slickrock is basically petrified sand dunes. It’s sandstone, and it’s common to hike, bike, or drive Jeeps on Slickrock in the Southwest.

Slickrock was treacherous to early pioneers because metal wagon rims and horseshoes struggled to get traction on the rock.

But today, our rubber soles, bike tires, and Jeep tires go together with Slickrock like peanut butter and jelly! It’s not slick at all unless it gets wet or has too much sand on it.

Slickrock is a blast for hiking and scrambling because it has so much grip.

Unlike hiking in the mountains where there is vegetation and trails are easily visible, the desert lacks vegetation and trails are often undetectable when hiking across Slickrock.

Even on well-established trails in the national parks, it is often easy to get off the trail.

So depending on who manages the land, trails are marked in different ways.

The National Park Service typically marks its trails with rock cairns. These are just little stacks of rocks to guide your way. The rule of thumb is that you should be able to see from one cairn to the next.

Note that these cairns aren’t very big. The park service doesn’t want them to be a focal point – just a subtle guide along your way.

Also, DO NOT knock over the cairns or establish new ones. This can lead others astray. The park service sends its rangers out to maintain the cairns often. What may appear haphazard to you is actually an orchestrated effort to keep you on the trail.

In order to keep you on the path and not ruin the soil (see below), the park service will often use deadwood or logs as borders on the trail.

So if you’re hiking and you see a random dead log on the ground in front of you, it is likely telling you not to cross it.

Sometimes they’ll use rocks to create a walking path to point you in the right direction.

Note: Juniper trees are hardy trees in the desert that often look dead (they actually prune themselves to conserve water). Sometimes Juniper roots will be in your way on the path. These might look like a border telling you not to cross. If they are embedded in the ground, it’s not a border – it’s a root. If it’s a random loose log, it’s probably a border.

Finally, sometimes paint markings on the Slickrock are used to guide your way. These are more common with land managed by the Bureau of Land Management. You’ll often find green paint markings – like stripes in the road – to show you the way.

Most desert hiking – at least on well-established trails – is delightfully easy in tennis shoes, cross-trainers, or trail runners. I can’t think of a time when I wore boots to hike in the desert.

It’s usually dry, so mud is rarely an issue. I like to have light footwear, not big and clunky boots.

However, it’s very easy for rocks to jut through the surface, and with strange Slickrock formations, many trails have uneven terrain.

For this reason, it may be nice to bring boots. They can provide stability and comfort when stepping on pointy rocks.

As I get older, I can feel those bumps a little more underneath my feet. I’m still resisting the boots, however, and I’ve found some shoes that are a compromise. Hokas and Brooks, as well as others, offer shoes with thicker soles and more support. They aren’t boots, but they even out the bumps better than my old Asics.

Dry washes are river beds without water. It’s common to hike in these dry washes because they provide a natural path. But they are usually very sandy or gravelly, and hiking in them can often be a slog.

They may be completely dried up forever, but more commonly they are sleeping giants.

When the rain comes to the desert, the ground doesn’t soak it up well due to the lack of vegetation. That water has to go somewhere, so it funnels into these dry washes, which turn to rivers momentarily. While we’re on the topic…..

Flash floods are definitely real, and they are incredibly dangerous.

Monsoon season is July, August, and September – Capitol Reef got hammered in 2022, flipping cars and injuring people. Zion National Park has multiple flash floods per year.

Flash floods can happen even on bright, sunny days, so it’s always a good idea to check with park rangers before heading out on the trail, or on the park website. If it’s raining upstream, you might see the results downstream.

If you’re hiking in or near a river, as in the case of Zion’s Narrows, look for debris in the river. If you see a sudden increase in logs, leaves, and other debris, get to high ground, because a flood may be coming.

The desert may look barren, but there are organisms living in the soil. You’ll often notice that the soil has a little crust on top.

This is called Cryptobiotic Crust, and it’s very delicate. It retains precious water and allows some plants to grow.

So please stay on the trail to avoid damaging the crust!

It’s super easy to take shortcuts in the desert due to the lack of vegetation, but it doesn’t mean you should.

If you’re visiting the desert in the American Southwest, buckle up because there are sooo many amazing natural wonders out here!

Most people want to see the best sites and still avoid crowds. We create detailed itineraries that give you a step-by-step game plan so you can get to the best places at the right times and love your trip. Most include an audio guide to tell you all about the area you’re visiting!

This site is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. We are compensated for referring traffic and business to Amazon and other companies linked to on this site.

Receive weekly newsletters updating you on the Best of the West including: essential travel tips, park updates, stories, and our favorite things to see and do.